'Battleship Potemkin': A Gift for Violence

I watched ‘Battleship Potemkin’ again the other day, on streaming video, after – well, a very long time. This 1925 communist propaganda film by Soviet director Sergei  Eisenstein draws loosely on historical events, the mutiny aboard a ship of the Russian imperial navy, during the failed 1905 revolution against the tsarist government. The “Odessa Steps” sequence – the most celebrated scene in the movie and all of film history – depicts a massacre by government troops of townspeople on the monumental staircase leading down to the harbor in the Black Sea port of Odessa.

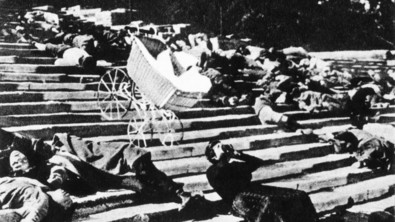

Eisenstein draws loosely on historical events, the mutiny aboard a ship of the Russian imperial navy, during the failed 1905 revolution against the tsarist government. The “Odessa Steps” sequence – the most celebrated scene in the movie and all of film history – depicts a massacre by government troops of townspeople on the monumental staircase leading down to the harbor in the Black Sea port of Odessa.

Western movie critics used to vote it the greatest film of all time, and, while it has slipped a little, the British Film Institute still had it up there in 2017, at number 11. This January 22nd Google devoted the Daily ‘Doodle’ on its search page to Eisenstein, exalting him as the father of the montage technique in film, and saying “His films were also revolutionary in another sense, as he often depicted the struggle of downtrodden workers against the ruling class.” This from a company whose founders, Larry Page and Sergey Brin, sit at the pinnacle of our ruling class, with a combined net worth of $100 billion.

I can’t now recall my feelings the first time I saw Potemkin. We had rented it from a distributor - in 35mm celluloid, on a big reel, in an aluminum can - for screening at one of my college's many ‘progressive’ student societies. Probably I was too busy feeling virtuous to pay it any mind.

Watching the Odessa Steps sequence again, though, I was engulfed by physical and emotional distress, a sudden constriction in my chest and throat, difficulty breathing, tension, and anxiety. Here are the townsfolk atop the stairway, cheering the revolted battleship. SUDDENLY – the word flashes on the screen – people start to run down the steps, a herd of antelope panicked by something unseen but terrifying. Only then do you see the lions, the white-coated troops marching forward at the head of the staircase. Here you see Eisenstein’s famous use of montage, the splicing together of jarring, disparate shots to create an intended psychological effect in the audience, revolutionary outrage in this case. The shots of bodies pitching forward, the fleeing crowd, soldiers firing, the close-up of a woman’s bloody face with her eye shot out – all this has been analyzed so well and so often by movie critics and directors I can add little.

But to what end is all this technical brilliance? I felt distressed and anxious, but not revolutionary outrage against the Tsarist regime. On reflection, I also felt disgusted to have been the object of a sort of master class on the manipulation of emotions. My distress and anxiety could have been manipulated for any purpose whatsoever, be it by communists, or Nazis, or, in our day, by Google and its advertisers.

David Thomson, the movie critic, says perceptively that the hook in Potemkin is not the overt political message but the loving depiction of violence:

“Potemkin does urge us not to hack down innocent citizens who have come to see the big show. It even maintains that it is shocking to expect sailors at sea to eat maggots.  But those things hardly amazed many audiences. What gripped them was this new, close-up scrutiny, this screening, of intolerable damage, to the extent that we watched it and came back for more and called it the height of cinematic art. It did this without ever drawing anyone’s attention to the ways the film celebrated the “relentless” chorus line of bayonet-bearing troops coming down the steps….What I am saying is that Eisenstein was as thrilled by violence as Hitchcock or Sam Peckinpah, and by the ways in which montage permitted it—just as Hitchcock could not have murdered Marion Crane [in Psycho] without the sharp blades of editing’s tools.” (David Thomson. 2012. ‘The Big Screen: The Story of the Movies’).

But those things hardly amazed many audiences. What gripped them was this new, close-up scrutiny, this screening, of intolerable damage, to the extent that we watched it and came back for more and called it the height of cinematic art. It did this without ever drawing anyone’s attention to the ways the film celebrated the “relentless” chorus line of bayonet-bearing troops coming down the steps….What I am saying is that Eisenstein was as thrilled by violence as Hitchcock or Sam Peckinpah, and by the ways in which montage permitted it—just as Hitchcock could not have murdered Marion Crane [in Psycho] without the sharp blades of editing’s tools.” (David Thomson. 2012. ‘The Big Screen: The Story of the Movies’).

Pauline Kael had made this observation much earlier, as an aside, in a 1967 review of ‘Bonnie and Clyde.’ She says of that movie’s director, Arthur Penn, that “he has a gift for violence, and, despite all the violence in movies, a gift for it is rare. (Eisenstein had it, and Dovzhenko, and Bunuel, but not many others.)” (Pauline Kael. 1968. ‘Kiss Kiss Bang Bang’).

There is also enormous bald-faced dishonesty about making a movie critical of Tsarist repression in the year 1925. By then, in a few brief years, the communists had already murdered, imprisoned and starved to death Russians on a scale many orders of magnitude greater than the pathetically inefficient and mild-mannered Tsarist regime managed in its entire history.

Writing about political executions under the Tsarist regime, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn says in ‘The Gulag Archipelago’ that “For a period of thirty years—from 1876 to 1904 … 486 people were executed; in other words, about seventeen people per year for the  whole country…. During the years of the first revolution (1905) and its suppression, the number of executions rocketed upward, astounding Russian imaginations, calling forth tears from Tolstoi and indignation from Korolenko and many, many others: from 1905 through 1908 about 2,200 persons were executed—forty-five a month.”

whole country…. During the years of the first revolution (1905) and its suppression, the number of executions rocketed upward, astounding Russian imaginations, calling forth tears from Tolstoi and indignation from Korolenko and many, many others: from 1905 through 1908 about 2,200 persons were executed—forty-five a month.”

Compare that to the productivity of the communists, says Solzhenitsyn: “in the twenty central provinces of Russia in a period of sixteen months (June, 1918, to October, 1919) more than sixteen thousand persons were shot, which is to say more than one thousand a month.” And this may be a vast underestimate. In the ‘Black Book of Communism”, Nicholas Werth estimates that the Cheka – the communist secret police – executed at least 10-15,000 people in just two months in the fall of 1918.